The Umayyad Dynasty (661-750 CE), the first dynasty to officially assume the title of Caliphate, was established in 661 CE by Muawiya (c. 602-680 CE), who had previously served as the governor of Syria under the Rashidun Caliphate, following the death of the fourth caliph, Ali, in 661 CE. The Umayyads firmly consolidated political power, effectively establishing the Caliphate’s authority by quelling rebellions with brute force, giving no quarter to those who incited uprisings.

They ruled over a vast empire, expanding it by adding newly conquered territories, including North Africa (beyond Egypt), Spain, Transoxiana, parts of the Indian subcontinent, and several islands in the Mediterranean (although many of these were eventually lost). Despite their successful territorial expansion, internal divisions and civil wars weakened their hold on power, and in 750 CE, they were overthrown by the Abbasids (r. 750-1258 CE), a rival Arab faction claiming descent from the Prophet’s uncle Abbas.

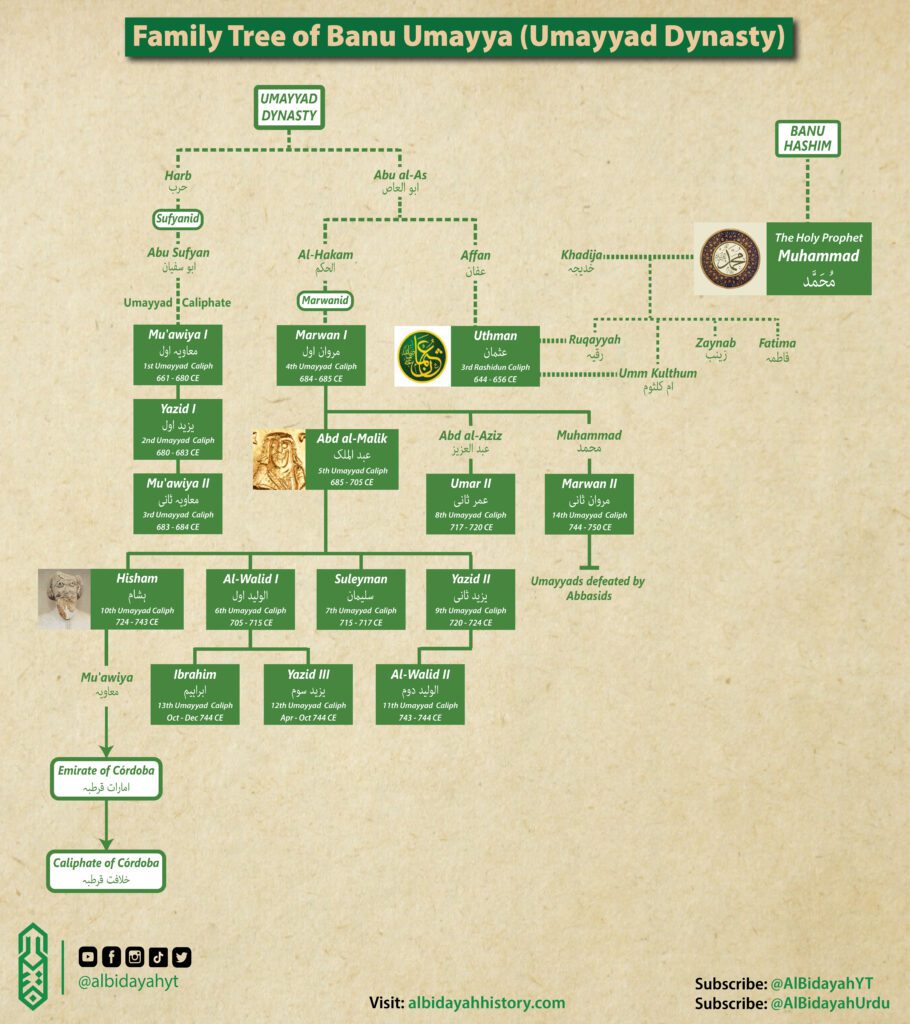

See Also: Banu Umayya (Umayyad Dynasty) Family Tree

Prelude

After the death of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad (l. 570-632 CE), Abu Bakr (r. 632-634 CE), a close companion of the Prophet, took the title of Caliph, thus forming the basis of the Islamic Caliphates. Abu Bakr was the first of the four initial caliphs, collectively referred to by mainstream Sunni Muslims as the Rashidun Caliphs. While Shia Muslims consider only the fourth, Ali (a close companion and son-in-law of the Prophet), to be the legitimate caliph.

During the Rashidun period, Islamic armies launched extensive conquests into Syria, the Levant, Egypt, parts of North Africa, the Greek archipelago, and the entire Sassanian Empire. These conquests began under Abu Bakr and were successfully continued by his successors Umar (r. 634-644 CE) and Uthman (r. 644-656 CE). However, Uthman proved to be a weak ruler and was assassinated by rebels in 656 CE. His death marked a turning point in Islamic history, as his successor, Ali (r. 656-661 CE), found himself struggling to control a fragmented empire while addressing the demand for justice for Uthman’s death.

MUAWIYA WAS A COUSIN OF UTHMAN; HE REFUSED TO SETTLE FOR ANYTHING LESS THAN THE EXECUTION OF HIS KINSMAN’S ASSAILANTS.

Ali faced considerable opposition, particularly from Muawiya, Uthman’s cousin and governor of Syria, who demanded retribution for his kinsman’s murder. This conflict led to the First Fitna (656-661 CE), a civil war that culminated in Ali’s assassination by an extremist faction called the Kharijites. These zealots also attempted to assassinate Muawiya but failed, leaving him with only minor injuries.

Muawiya I

Muawiya’s (r. 661-680 CE) lineage, known as the Sufyanids (after his father Abu Sufyan) or sometimes as Harbites (after his grandfather Harb), was marked by his political cunning and strong diplomacy, preferring bribery to open warfare. He convinced Hasan (l. 624-670 CE), Ali’s son and successor in Kufa, to abdicate in his favor in exchange for a generous pension. However, Muawiya did not hesitate to eliminate perceived threats, and many Muslim historians link him to the death of Hasan, who was allegedly poisoned by his wife in 670 CE.

Muawiya’s 20-year reign, from his capital in Damascus, was the most stable period the Arabs had experienced since the death of Umar. His administrative reforms were significant, including the establishment of a police force (Shurta), personal bodyguards, and diwans (local administrative units) similar to those established by Umar. He initiated military campaigns into modern-day Pakistan and Afghanistan, and in the west, he extended the empire’s boundaries to the Atlantic coast of Morocco. Despite regaining some territories lost to the Byzantines, most of these gains were reversed after his death due to internal strife.

Yazid I & the Second Fitna

The problems began when Muawiya appointed his son Yazid (r. 680-683 CE) as his successor, a decision that was met with widespread resentment as Arabs were not accustomed to hereditary rule. This discontent was most notably expressed by Husayn ibn Ali (l. 626-680 CE), Hasan’s younger brother, and Abdullah ibn Zubayr (l. 624-692 CE), the son of a close companion of Prophet Muhammad.

In 680 CE, Husayn, encouraged by the people of Kufa, marched towards Iraq with the intention of rallying support and then advancing on Damascus. However, Yazid imposed a lockdown on Kufa and dispatched an army under his cousin, Ubaidullah ibn Ziyad (d. 686 CE), to intercept Husayn. The two forces met at Karbala near the Euphrates, where Husayn and his small force of around 70 men (mostly family members and close associates) made a heroic stand before being massacred, and Husayn was beheaded. This event marked the Second Fitna (680-692 CE), the second major civil war in Islamic history.

TODAY YAZID IS REMEMBERED AS PERHAPS THE MOST NEGATIVE FIGURE IN ISLAMIC HISTORY.

Yazid then turned his attention to Medina, whose residents had rebelled against him due to disgust over his character and actions, leading to the Battle of al-Harra (683 CE). After crushing the opposition, Medina suffered plunder, pillage, and alleged atrocities by Yazid’s Syrian forces. The Syrian army then proceeded to Mecca, where Abdullah ibn Zubayr had established his own rule.

The city was besieged for several weeks, and the Ka’aba’s covering caught fire during the conflict. Although Yazid’s army withdrew after his sudden death in 683 CE, the damage done by his forces left a lasting scar on the Muslim community. Abdullah ibn Zubayr continued his revolt for another decade, proclaiming himself Caliph (r. 683-692 CE) and gaining support in Hejaz, Egypt, and Iraq, while the Umayyads barely retained control of Damascus.

Today, Yazid is remembered as one of the most reviled figures in Islamic history. His son, Muawiya II (r. 683-684 CE), briefly succeeded him but distanced himself from his father’s actions and died a few months later, marking the end of the Sufyanid branch. With the exception of Damascus, the entire Umayyad realm was in chaos.

Marwan ibn Hakam, The Marwanids

Marwan ibn Hakam (r. 684-685 CE), a senior member of the Umayyad clan and a cousin of Muawiya, assumed power with a promise to pass the throne to Yazid’s younger son, Khalid, after his death. However, Marwan did not intend to keep this promise, and the empire came under the control of the Marwanid branch (the house of Marwan), also known as the Hakamites (after Marwan’s father Hakam). Marwan recaptured Egypt, which had revolted and joined Abdullah’s faction, but he died nine months later in 685 CE, leaving his brilliant son Abd al-Malik (r. 685-705 CE) to deal with Abdullah’s revolt.

Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan

In 685 CE, Al Mukhtar (l. c. 622-687 CE) initiated a revolt in Kufa, aligning with Abdullah against the Umayyads. Al Mukhtar systematically targeted those responsible for Husayn’s death. An army led by Abd al-Malik under Ubaidullah was defeated by the combined forces of the Kufans and Zubayrids, and Ubaidullah was killed.

![Gold dinar minted by the Umayyads in 695, which likely depicts Abd al-Malik.[a]](https://albidayahhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/First_Umayyad_gold_dinar_Caliph_Abd_al-Malik_695_CE-1024x1014.avif)

Al Mukhtar then declared his intention to establish an Alid Caliphate, backing one of Ali’s sons, Muhammad ibn al-Hanaffiya (l. 637-700 CE), who was not from Fatima, the Prophet’s daughter. This led to a rift with Abdullah, who also claimed the Caliphate. Abd al-Malik bided his time as his rivals weakened one another. In 687 CE, Al Mukhtar was killed by Abdullah’s forces during the siege of Kufa. Although Al Mukhtar perished, his revolt laid the foundation for the transformation of Shi’ism from a political group into a religious sect.

With the threat in Kufa neutralized, Abd al-Malik shifted his focus to Mecca, sending his loyal and ruthless general, Hajjaj ibn Yusuf (l. 661-714 CE), to subdue Abdullah. Despite being outmatched, Abdullah refused to surrender and died fighting in 692 CE, marking the end of the civil war.

While Abd al-Malik faced criticism for Hajjaj’s harsh methods, he is credited with restoring stability and centralizing power in the empire. Notably, he Arabized the entire administration, which aided in the spread of Islam, and introduced official coins for the empire.

The construction of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem (691-692 CE) took place under Abd al-Malik, possibly to establish a counterbalance to Abdullah, who controlled the Ka’aba at the time. During his reign, the entirety of North Africa, including Tunis, was permanently brought under Umayyad control by 693 CE. The Berbers, who converted to Islam, played a crucial role in carrying the religion to Spain during the reign of Abd al-Malik’s son.

Al-Walid I & Conquest of Spain

After Abd al-Malik’s death, his son Al Walid I (r. 705-715 CE) ascended to power, further expanding the empire’s boundaries. Hajjaj continued to exert influence, appointing two of his protégés, Muhammad ibn Qasim (l. c. 695-715 CE) and Qutayba ibn Muslim (l. c. 669-715 CE), to conquer parts of modern-day Pakistan and Transoxiana, respectively.

The Muslim conquest of Spain began in 711 CE, led by the Berber general Tariq ibn Ziyad, who landed on the Iberian Peninsula at a location that now bears his name: Gibraltar. Tariq defeated a numerically superior Visigothic army led by King Roderic (r. 710-712 CE) at the Battle of Guadalete, after which the region was left vulnerable to further conquest.

Musa ibn Nusayr (l. 640-716 CE), the governor of Ifriqiya (North Africa beyond Egypt), reinforced Tariq’s forces, and together they conquered most of Al-Andalus (Spain) by 714 CE. Musa was on the verge of launching an invasion of Europe through the Pyrenees when, for reasons that remain unclear, the Caliph ordered both Musa and Tariq to return to Damascus.

Sulayman ibn Abd al-Malik

Al Walid attempted to appoint his own son as his successor rather than his brother Sulayman, who was next in line per their father’s agreement. Sulayman resisted, and Walid died before he could secure his son’s succession. Sulayman (r. 715-717 CE) then assumed the caliphate, but his brief reign was marked by failure. Sulayman harbored deep resentment towards the late Hajjaj, releasing many of those held in Hajjaj’s prisons.

Sulayman also turned his ire on Hajjaj’s loyal subordinates, many of whom were killed. He then set his sights on Constantinople, launching a massive campaign to capture the Byzantine capital in 717 CE. The venture ended in disaster, marking the first significant setback against the Byzantines and halting Umayyad expansion. Nearing his death, Sulayman realized that his sons were too young to succeed him and appointed his pious cousin Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz as his heir.

Umar II and Yazid II

Umar II (r. 717-720 CE) ruled for only three years before being poisoned by his family, likely because of his unwavering commitment to justice and Islamic principles. His actions, including ending the public cursing of Ali, facilitating conversions, and halting attacks on peaceful neighboring empires, earned him posthumous acclaim as the fifth Rashidun Caliph.

Umar II halted all military campaigns, recognizing that the empire needed internal reform before further expansion. He also negotiated with non-Arab Muslims (Mawali), who had opposed Umayyad rule due to being violently repressed. Had Umar II been given more time, he might have succeeded in preventing the Abbasid uprising, as the Mawali and Shia Muslims of the eastern provinces were key supporters of the Abbasid revolt.

Umar’s successor, Yazid II (r. 720-724 CE), another son of Abd al-Malik, proved to be no better a ruler than the first one to bear his name. Whilst he was busy fondling with his favorite concubines in his harem, his ineffective governors had lost all control of the empire. Fortunately for the Umayyads, he died just four years after assuming control.

Hisham and Restoration of Order

Yazid’s brother and successor, Hisham (r. 724-743 CE), inherited an empire torn by civil wars. Hisham dedicated his energies to restoring stability and reinstating many of the reforms introduced by Umar II that Yazid II had abandoned. Some of his military expeditions were successful, others not so much: a Hindu revolt in Sindh (a province in modern-day Pakistan) was crushed, but a Berber revolt broke out in the western parts of North Africa (modern-day Morocco) in 739 CE.

The Berbers had been stirred up by the fanatical teachings of Kharijite zealots (a radical and rebellious sect of Islam) and caused a great deal of damage, most notably, the deaths of most of the Arab elites of Ifriqiya at the Battle of Nobles (c. 740 CE) near Tangier. Attempts to crush the rebellion did not even come close to complete the objective, but the disunited Berbers soon disintegrated (743 CE) after they failed to take the core of Ifriqiya, the capital city of Qairouwan, but Morocco was lost for the Umayyads.

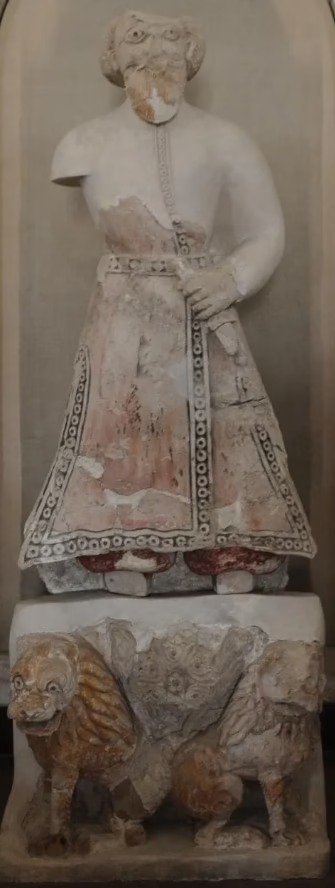

Khirbat al Mifjar, Jericho

Al Andalus had also descended to anarchy, but Hisham was successful there. Under an able general named Abd al-Rahman al-Ghafiqi, the province was restored to order but further expansion into Europe was checked after the defeat at the Battle of Tours (732 CE) against the Franks under Charles Martel (r. 718-741 CE).

The Third Fitna

After Hisham’s death in 743 CE, the empire was brought to a civil war. Walid II – a son of Yazid II ruled from 743-744 CE, before being overthrown and killed by Yazid III (d. 744 CE) – a son of Walid I. This sparked the Third Fitna (743-747 CE), the third civil war in Islamic history as many tribes had also started revolting against the establishment amidst the chaos. Yazid III died just six months later and was succeeded by his brother Ibrahim who only managed to rule for two months before being overthrown by the elderly Marwan II (r. 744-750 CE) – a grandson of Marwan I.

Marwan II was a strong military commander but lacked diplomatic skills, instead he crushed the uprisings with brute force and brought an end to the Third Fitna in 747 CE. However, the Abbasids (an Arabian faction that claimed to be descendants of the Prophet’s uncle: Abbas), had gained the support of the people of Khurasan (in Iran). His empire was not in a state to face a large scale uprising; his army was exhausted after years of warfare, the failing economy did not allow him to recruit more troops, and ineffective governors failed to realize the gravity of the Abbasid threat until it was simply too late.

By the end of 749 CE, most of the eastern states had displayed the black standards of the Abbasids and the resentful tribes that he had subjugated with force were also allying with them. He faced the bulk of the Abbasid army near the Zab River (750 CE), where his army was routed and he was forced to flee. He escaped to Egypt, intending to muster up his forces from western provinces, but the Abbasids caught up with him and killed him. Umayyad rule was over, and the first Abbasid ruler Abu Abbas (r. 750-754 CE) was declared the new Caliph in Kufa.

Umayyad rule ended with Marwan’s death but Abd al-Rahman carried on his family’s hold on Spain.

End of the Umayyads

The Abbasids showed no mercy to the Umayyads. All male members were killed, with only a few managing to escape. The Abbasids desecrated Umayyad graves in Damascus, exhuming and destroying the remains, except for those of Umar II, whose grave was spared due to his favorable reputation. The Abbasids invited the surviving Umayyads to a supposed reconciliation dinner, only to have assassins club them to death at the caliph’s signal. One survivor, Abd al-Rahman I, grandson of Hisham, escaped and made a perilous journey to Al-Andalus, where he established the Emirate of Cordoba in 756 CE, a rival to the Abbasid Caliphate in elegance and grandeur.

Conclusion

The Umayyads were the first dynasty to transform the caliphate into a hereditary institution. They brought centralization and stability to the realm and continued the empire’s swift military expansion. However, their flaws and misdeeds tarnished their reputation. Yazid I, in particular, committed grievous offenses against the family of Ali and the people of Medina and Mecca, making him one of the most reviled figures in Islamic history. His actions, especially the massacre of Husayn at Karbala in 680 CE, are commemorated annually by Shia Muslims during the festival of Ashura.

Yazid’s actions have been extended over to the whole dynasty, and since most of the Umayyad caliphs were more or less secular and led luxurious lives (save a few such as Umar II and Hisham), they were viewed as being godless by pious Muslims of their time. Contemporary historians tend to glorify them while many Muslim historians (but not all) tend to demonize them. Despite their many flaws, the Umayyads were effective rulers and made notable contributions not only to the empire but – perhaps unintentionally, with the Arabization of the empire – to Islam itself.